Unvaxxed and Unbeaten: The Story of Eric Velvick

This Brisbane retiree was jailed for 18 days for entering his home state while unvaccinated. He stuck to his guns, fought the charges, and won.

Eric Velvick is not a criminal and never has been, but that didn’t stop him from being treated like one when he attempted to cross the Queensland border in January 2022. The 71-year-old Brisbane resident was arrested, charged and locked up for a total of 18 days, 14 of which were spent in one of the country’s most notorious prisons. Eric wasn’t allowed to contact family or obtain legal aid, and when he refused to plead guilty, a magistrate sought to have him diagnosed as mentally incompetent.

This is the story of how one free-thinking retiree stuck to his guns, fought the charges that had been laid against him, and forced the police to eventually back down.

All Eric wanted to do was go home.

It was January 6, 2022, and Eric was preparing to leave Canberra, having just spent the festive period with his son, daughter-in-law and grandkids. Two weeks earlier he’d driven from Brisbane to Canberra without incident, and he was hoping that his return trip would be equally uneventful.

The Queensland border was open to both domestic and international travellers at the time, but only those who were fully vaccinated. The public health orders dictated that Eric, as an unvaccinated person, wasn’t eligible to re-enter his home state, despite the fact that the vaccines had long ago ceased to be effective at preventing infection.

Eric concedes that he didn’t know what the rules were at the time — and that frankly, he didn’t care. He was firmly of the view that unelected bureaucrats had no right to tell him where he could and couldn’t travel within his own country.

“My daughter-in-law was worried that I’d run into trouble at the border,” Eric says. “She printed off some paperwork on the night before I left and insisted that I take it with me.

“I took it and said, don’t worry, I’ll get across the border OK. I’ll be fine.”

It was a remark that proved ill-fated. Eric was pulled over at a border checkpoint on the Castlereagh Highway and asked to provide a border pass and proof of vaccination. He offered the paperwork that his daughter-in-law had printed, but the police officer quickly dismissed it as invalid.

“He kept asking for my border pass,” Eric recalls. “When I said that I didn’t have one, he told me to go back the way I came. I said to him, look, I’m a Queensland resident. But he wasn’t having a bar of it.”

Not wanting to cause a scene, Eric turned around and drove back to Lightning Ridge, a small town just south of the Queensland border. He decided to camp there overnight and plan his next move.

He momentarily considered returning to Canberra — but as the night wore on, he grew increasingly frustrated. He couldn’t stomach the fact that he was being denied entry into his own home state based on rules that had never been voted on, and which evidently made zero sense. The more he thought about it, the angrier he got.

“At some point in the night I just said to myself, that’s it, I’ve had enough. I’m not going to take this bullshit anymore.

“I decided to stand up for myself — to cross the border, one way or another.”

The next morning he attempted to enter Queensland again, this time via a different route. The result was the same: Eric was stopped at a checkpoint, asked to provide paperwork, and then told to turn around — but this time, he stood his ground.

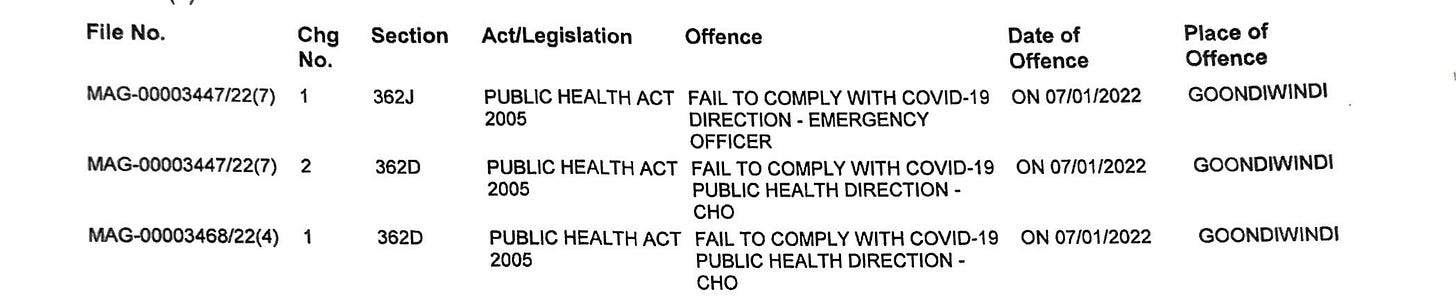

“I told them I’m not going back,” he says. “I told them to either let me through or arrest me. And so they arrested me.”

So began the first of Eric’s 18 days of imprisonment. He was thrown in a paddy wagon and driven to the Goondiwindi police station, where he stayed for a few hours before being transported to the station in Toowoomba.

“Straight away they tried to make me take the jab,” Eric says of his time in Toowoomba. “They said that if I refused, I’d have to go into isolation. I refused, of course, and so they put me in a cell by myself.”

Eric was confined to the cell for two full days. “They didn’t let me out for anything,” he says. “No exercise, no showers, nothing. They just brought me food a few times a day. That was it.”

Eventually the officers told Eric that he could mix with other people provided he wore a mask. Eric agreed, and was subsequently moved to a larger cell that he shared with “three or four other guys”.

On his fourth day in Toowoomba, Eric was taken into a separate room to appear remotely before a magistrate. The magistrate asked him whether he wanted to plead guilty to his charges. At this point Eric had not received any form of legal aid despite requesting it on multiple occasions. He felt as though they were trying to manipulate him into admitting guilt.

“I didn’t know what to say, so I just told him that I didn’t think I’d done anything wrong,” Eric remembers. “I said, I haven’t broken the law. All I did was try to drive home after spending Christmas with my family.”

When Eric refused to plead guilty, the conference call abruptly ended. The officer supervising the hearing said that “he’d never seen that happen before”. Eric later found out that the magistrate had insisted upon getting him psychiatrically evaluated.

“His plan was to get me certified as mentally incompetent. He was pushing the police to bring a psychiatrist in to say that I wasn’t capable of making my own decisions. They didn’t go along with it, thankfully.” Eric believes that the magistrate was attempting to override his refusal to plead guilty. “They were trying to intimidate me, but I didn’t go along with it, and I think they started to get really frustrated.”

Later that night, Eric was notified that he’d been scheduled for a transfer to Arthur Gorrie Correctional Centre, a high-security remand centre in Brisbane. Arthur Gorrie is notorious for its history of bashings, attempted suicides and riots. An ABC investigation published in 2018 described the privately owned facility as “overcrowded, increasingly violent and unsafe”.

For Eric, the discomfort began before he even arrived. He was driven from Toowoomba to Brisbane in the back of a paddy wagon alongside another inmate. “It was cooking in there,” he recalls. “There was no air circulation. We had no room to move, and we were handcuffed the entire time.”

Upon arriving at Arthur Gorrie, Eric was forced to strip naked and put on his prison garb. While the guards were taking his finger prints, he asked again whether he could speak to a lawyer. The guards denied the request, saying that the right to legal aid doesn’t apply under the Covid legislation.

Eric then asked if he could at least call his son. This request, too, was denied. “I couldn’t contact anyone,” Eric says, his exasperation still evident even after all this time. “You read about all these rights that you supposedly have … but once the correctional people got hold of me, I had no rights whatsoever. They just said ‘do as you’re told’.

“I felt like they were using the Covid legislation to make up their own rules on the fly.”

Eric’s sleeping arrangements at Arthur Gorrie were claustrophobic. He was forced to sleep on a mattress on the floor of a one-person cell while another inmate slept on the bed.

“The cell was made for one person, but they had two of us in there.” Eric says that he was confined to this overcrowded cell for most of his time at the facility. “They didn’t let me out until my last few days. Until then we weren’t allowed to exercise, not even a quick walk. We had to pace back and forward in the cell.”

Eric’s experience is consistent with Arthur Gorrie’s reputation for overcrowding — he did not, however, find his fellow inmates to be particularly aggressive or hostile. “I couldn’t fault the inmates,” he admits. “To be honest, they were much nicer than the guards.” He says his cellmate even offered to sleep on the floor so that Eric could have the bed, an offer he gratefully accepted.

Camaraderie notwithstanding, Eric was eager to be set free — and on January 25, 18 days after he was arrested, he finally got the chance. He was pulled out of his cell for another remote hearing, this time with a different magistrate who was much more professional.

“This guy didn’t muck around,” Eric says. “He read out what I was in for and said, would you like to get out on bail? I said, of course I would. And that was that.”

A follow-up court date was set, and at 6pm that evening Eric was released. He walked back into society with his head held high and dignity intact, proud to have finally found his way home.

Once out, Eric wasted no time in preparing to fight his case. He found a solicitor and instructed her to formalise his not guilty plea, which she did. Eric’s next court date was then scheduled at Goondiwindi, 350 kilometres from Brisbane, a move which his solicitor believes was motivated by spite.

“We came to the conclusion that they were just being arseholes,” Eric says. “They made me drive all the way back to Goondiwindi instead of having the hearing here at Sandgate, seven kilometres from my home.”

When the court date rolled around, Eric’s solicitor drove four hours to attend — the prosecutors, however, did not. Eric and his solicitor found out on the day that the police had decided not to pursue the case.

“And just like that,” Eric says, “all of my charges were dropped.”

Eric suspects that the police locked him up hoping that he’d panic and plead guilty — and when he didn’t, they grew nervous. In his view, they dropped the charges because they didn’t want the public health orders to be scrutinised in court. “I think they came to their senses and realised that what they did to me was never actually legal. So when the time came to defend their actions, they didn’t even show up.”

Eric felt vindicated by the outcome, but confesses that it came at a cost. He not only had to pay for his legal representation, but also jump through hoops to get his age pension reinstated.

“Centrelink cut my payments while I was in prison because I was apparently getting free board and lodging at the state’s expense,” he says with a dry laugh, before comparing his treatment with that of the large corporations that made record profits after receiving billions of dollars through the federal government’s JobKeeper program. “It’s funny how they got given truckloads of money and the government let them keep it — but when it’s an ordinary person like me, they claw back every cent.”

Despite everything, Eric hopes that his story will inspire other Australians to stand up for themselves when it’s their turn to do so.

“Hardly anyone took a stand during the pandemic,” he laments. “I know a lot of smart people, people I respect, who didn’t speak up when they should have. They just believed what the media was saying, or pretended to believe it.

“You need to be skeptical, to call out bullshit when you see it — because if you don’t, they’ll just walk all over you.”

The Winston Smith Initiative is supporting freedom fighters like Eric by campaigning for a truly independent Pandemic Royal Commission. If you want to join the fight, consider subscribing to this publication — it only costs about $2/week, and it makes a huge difference to the sustainability of our movement.

minor details - since federation there are no borders and given the experimental nature of the jabs that we know (before) and (after) don’t work just what crime has one committed? answer - the beaurocrats / politicians are the ones who need to be charged and brought to justice… Nuremberg 2.0 comes to mind…

I’d be suing the arse off the police, the courts and anyone else who put you in this position. They all have been unlawful in their dealing with you. I would be livid if this happened. It was a bloody virus not the Black Plague ffs🤬